How to Ask for Help Without Feeling Bad About It

I dreamed up this article while doing my quarterly car deep clean in between annual professional cleans, which means I don’t wait until my help need is EMERGENCY RESPONSE level before calling in the professionals.

The car detailer showed up at my house with a sunny attitude and one regular-sized vacuum.

I have twins. The seats are cloth. I'm type B. We eat in the car constantly. I'd been meaning to get the car cleaned for... a while. I told him exactly what he was walking into. I did not sugarcoat. He gave me the pat-pat tone and laughed. "Ma'am, you have no idea what kind of disasters I've seen. I can make any car look good as new, I'm not worried."

Then an hour after he arrived, he sent me an accidental text that I was fairly certain was meant for his colleague. But… it WAS for me. He was that surprised.

"This car is a fucking disaster."

It took him AND another guy he had to call in for reinforcements an additional three hours to "drill the carpets" and perform many other loud and dramatic services to get this thing looking presentable again.

A similar thing happened with our lawn. The mower broke and we tried all kinds of ways to fix it ourselves. By the time we finally hired someone, the yard had become a genuine jungle. The poor underestimating guy who showed up with a regular mower and a whole lot of confidence hacked through that wilderness into the dark of night.

Now. You could say the theme here is men not believing women, of men underestimating the size of a job. Maybe. But the bigger pattern is mine. By the time I finally asked for help with either of these things, the task had grown so far beyond normal range that of course anyone would underestimate it. I'd turned a maintenance task into an emergency response.

And if you're reading this thinking, "OK but that's just a car and a lawn" — I'd gently invite you to consider whether this pattern shows up in places that matter more. Your work. Your relationships. Your body. Your mental health.

Because here's the part that interests me most as a coach. The thing keeping most of us from asking for help isn't logistics. It's that asking for help feels gross. Vulnerable. Needy. Weak. Like admitting something you'd rather not admit. And so we don't. We wait. We handle it. We let the jungle grow. And then we wonder why, by the time help finally arrives, everything feels so much harder than it should.

A Pattern That Makes Perfect Sense (Until You’re Losing Your Mind)

Here's what this tends to look like in practice, and maybe some of it sounds familiar.

At home, you've been carrying the full mental load — the schedules, the backup plans, the emotional temperature of every person in the household — and you don't mention that you're drowning until you're sobbing in the bathroom after snapping at your kid for asking what's for dinner. (If that last part hit close, I wrote a whole piece about default parenting patterns and why they form.)

At work, you've taken on a project that quietly ballooned beyond your capacity three weeks ago, but you didn't flag it because you were still convinced you could muscle through. By the time you finally say something, your boss has to do triage — and you feel terrible for "letting it get this bad."

In relationships, you haven't told your friend that you've been struggling because you don't want to burden her. So she has no idea. And you're lonely, and also a little resentful that she hasn't noticed, which is unfair but real.

In your body, you've been ignoring the joint pain, the insomnia, the digestive issues, the hair shedding, the jaw clenching — until something forces you to a doctor, who tells you your cortisol is through the roof and asks, gently, how long this has been going on.

The answer is always longer than you thought. Because the early signals didn't feel like "enough" to justify asking for help.

This isn't a personality flaw. Research on help-seeking behavior consistently shows that one of the biggest barriers to asking for support is the preference to handle things independently — particularly among high-achieving women. A 2025 meta-analysis in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry found that across 14 studies examining barriers to help-seeking, nearly half of participants preferred to solve problems by themselves.

Other top barriers included not perceiving a need for help until things were severe, concerns about stigma, and simply not knowing where to start.

If you've ever had the thought "I should be able to handle this" while things quietly got worse around you — that tracks. It makes complete sense. And it might also be worth looking at.

Why Asking for Help Feels So Bad

There's a specific sequence that tends to play out for folks who carry more than their share, and it's worth naming because it helps explain why this isn't something willpower alone can fix.

Your nervous system learned early that self-reliance equals safety. For many high-achieving, over-responsible people, the capacity to handle everything independently didn't start as a personality trait — it started as an adaptation. Maybe you were the kid who figured things out because the adults around you couldn't or wouldn't. Maybe asking for help was met with disappointment, dismissal, or the message (spoken or not) that needing support was weak. Maybe you grew up in a family where someone else's needs always came first, and you learned to be invisible about your own.

Dr. Gabor Maté writes extensively about this in When the Body Says No, describing how compulsive self-reliance develops as a coping mechanism in childhood and then embeds itself so deeply that we lose the ability to even notice we need help. He puts it plainly — and I think about this often with my clients — one way to avoid ever feeling rejected is to never ask for help, to never admit what might feel like weakness, and to believe you're strong enough to handle everything alone.

The brain's threat detection system reinforces the pattern. When your early experiences taught you that vulnerability is dangerous, your amygdala — the brain's alarm system — files "asking for help" in the same category as "walking into traffic." It's not a conscious calculation. It's a physiological response. Your nervous system activates a low-grade stress response at the very thought of admitting you need support, and you interpret that stress as confirmation that asking would be a bad idea.

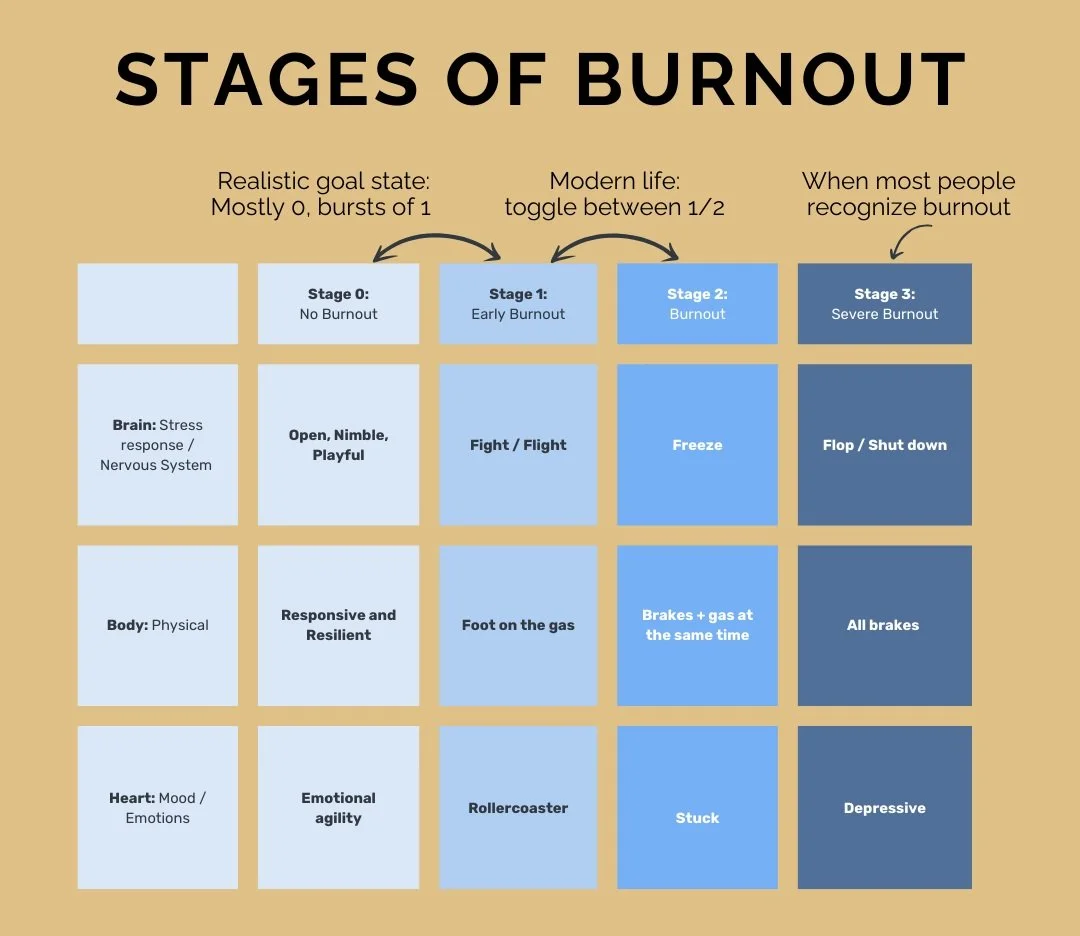

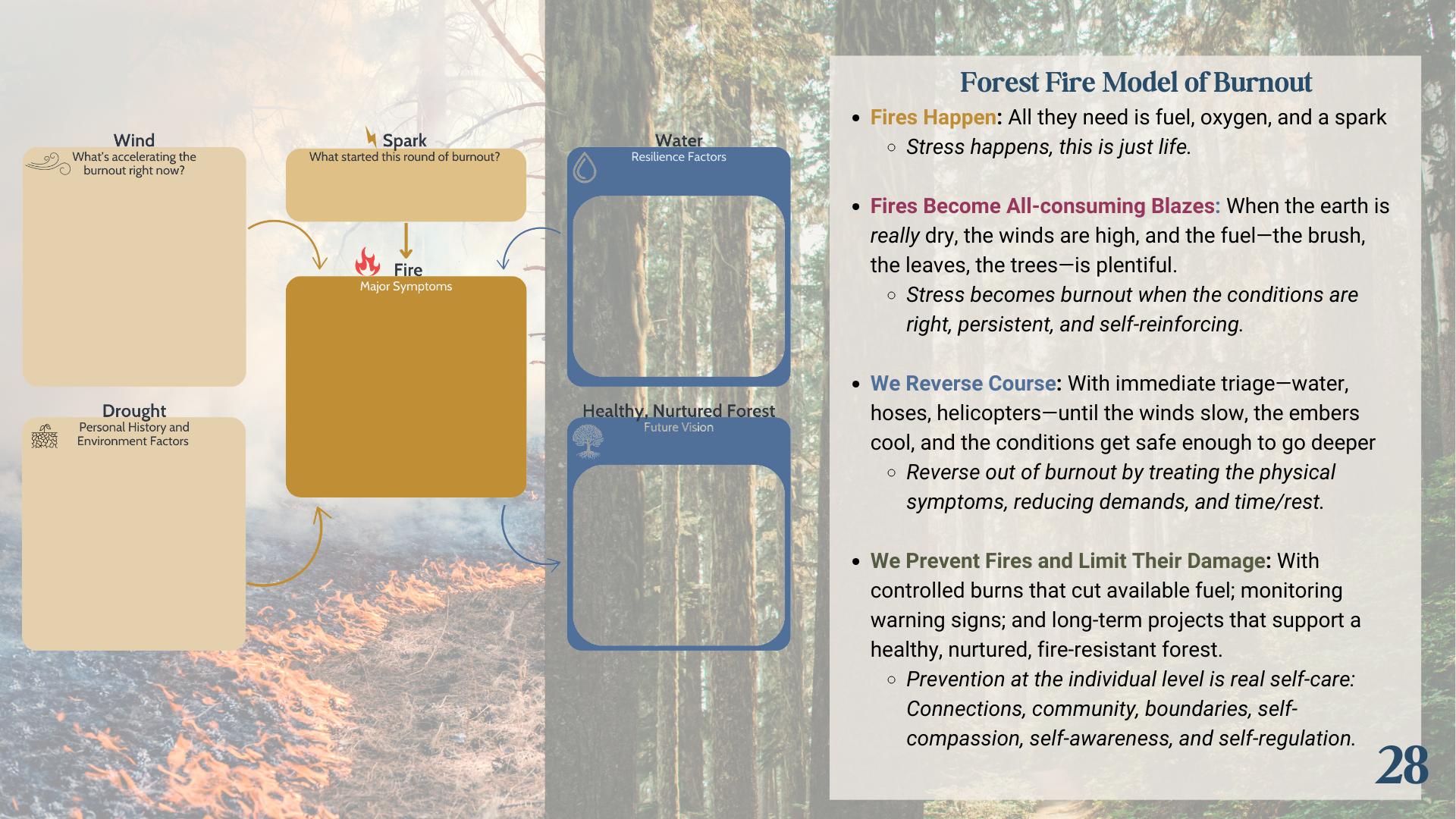

This connects directly to what I call the Forest Fire Model of burnout. Hyper-independence is one of the most common "drought conditions" — the long-term, below-the-surface factors that make someone's internal landscape vulnerable to fire. If you've spent decades building a life where you never need anyone, the ground beneath you is very, very dry. And any spark — a job change, a health scare, a season of parenting that pushes you past your capacity — can turn into a full blaze fast.

Competence becomes its own trap. Fiona Lee's research on "The Social Costs of Seeking Help" found that people who are perceived as highly competent face greater social costs when they ask for support — they're judged more harshly for it. So the better you are at holding everything together, the higher the invisible penalty feels for admitting you can't. This creates a vicious cycle. You get better at managing, people rely on you more, the bar rises, and the gap between "I'm fine" and "I'm drowning" narrows until there's no gradual middle ground — just a cliff.

And here's something I see constantly in coaching. Joe Hudson, founder of Art of Accomplishment, describes what he calls the Golden Algorithm — the pattern where the specific way you try to avoid an emotion ends up creating more of that exact emotion in your life. When you avoid the vulnerability of asking for help because you don't want to feel needy or burdensome, you end up alone with an escalating problem — which makes you feel more needy and burdensome when you finally have to ask. The strategy designed to protect you from the feeling creates a bigger version of it down the road.

I see this play out with clients regularly. One woman — let's call her Dani — came in because she was furious at everyone in her life. Not for anything specific. Just a diffuse, icy rage. Her partner wasn't anticipating what she needed. Her team wasn't picking up on things she hadn't explicitly asked for. Her kids weren't being independent enough. When we started mapping her burnout using the Forest Fire framework, a pattern emerged that she'd never seen before — the drought conditions in her map were almost entirely about self-reliance. She had built an entire identity around not needing anyone.

And the cruelest part. The more competent and self-sufficient you appear, the less likely people are to offer help unprompted. So help doesn't come. Which confirms the belief that it was never going to come anyway. Which deepens the pattern.

I wrote recently about how "I don't deserve" fuels this exact cycle — the way an old belief about worthiness quietly becomes the engine running your overfunctioning. It might be worth reading alongside this one if that feels resonant.

How You're Accidentally Training People Not to Help You

This is the section I almost didn't write because it's uncomfortable. But it's one of the most important dynamics I see in coaching, and it doesn't get talked about enough.

When you're hyper-independent — when you take over tasks, redo things people did "wrong," brush off offers of support, or make yourself genuinely hard to help — the people around you learn something.

They learn that not helping is what you actually want.

It's not manipulative. It's not intentional. But it's real.

Think about it from their perspective. Your partner offers to handle dinner and you hover, redirect, and eventually take over because they used the wrong pan. Your colleague offers to take something off your plate and you say "It's fine, I've got it" with a tone that communicates anything but fine. Your friend asks how you're doing and you say "Good! Busy!" with a bright smile that leaves no opening for follow-up.

Over time, the people around you get a very clear message, even if it's the opposite of what you're feeling inside. She doesn't need help. She doesn't want it. And when we try, it goes badly. So they stop trying. Not because they don't care, but because they've been trained — by your behavior, not your words — that stepping back is the safest move.

This is a version of what psychologists call learned helplessness, originally studied by Martin Seligman and Steven Maier in the 1960s. The classic research showed that when individuals experience repeated situations where their actions don't seem to matter, they eventually stop trying — even when circumstances change. In relationships, this can look like a partner who used to offer help all the time and gradually stopped, or a team that waits for explicit instructions rather than taking initiative, or kids who've learned to stay out of mom's way when she's in "handling it" mode.

The dynamic works like this, and I want to lay it out because I think seeing the mechanism helps.

You overfunction. You carry too much, do too much, manage too much. Often because you genuinely believe it won't get done right otherwise, or because the discomfort of delegating feels worse than the exhaustion of doing it yourself.

Others underfunction in response. Not because they're lazy or incompetent, but because your system doesn't leave room for them. When you consistently take over, people's competence and initiative atrophy. (The Bowen Center's work on overfunctioning/underfunctioning dynamics describes this as one of the most predictable patterns in family systems theory.)

You interpret their passivity as proof. "See? If I don't do it, nobody does." Which feels like evidence that you can't ask for help, because the help isn't there. But the help isn't there because you systematically, unintentionally, removed the conditions for it to develop.

The belief deepens. Now you're more self-reliant. They're more passive. And the gap grows.

Here's where it gets interesting from a research perspective. The Pygmalion effect — the well-documented psychological phenomenon that people tend to rise (or fall) to the level of expectations placed on them — applies here directly. When you expect that no one can handle things the way you can, you communicate that expectation through a thousand tiny signals. And people receive those signals and adjust accordingly. But the reverse is also true. When you communicate genuine belief in someone's capability and give them real room to step up, adults often rise to meet those expectations.

I've watched this in client after client's lives. When Dani started communicating to her partner — really communicating, with specificity and genuine trust — that she needed him to handle Saturday mornings with the kids, fully, without checking in, without her hovering... he fumbled at first. The kids ate cereal for dinner once. But within a few weeks, he'd built his own system. He was competent. He'd always been competent. He just hadn't had the actual space to demonstrate it because she'd been standing in the way, trying to protect everyone from an imperfect outcome.

This doesn't mean the people around you will always step up. Some won't. Some genuinely can't. But in my experience, a surprising number of them were just waiting for real permission — not the kind where you say "go ahead" while visibly clenching — but the kind where they can feel that you actually trust them.

So What Are We Actually Avoiding?

I want to go a little deeper here, because I think this is the layer most blog posts about asking for help don't touch.

Joe Hudson has this line that I come back to constantly in my work. He says, "Joy is the matriarch of a family of emotions, and she won't come into a house where her children aren't welcome." (Art of Accomplishment podcast)

What he means is that if you've closed the door on certain emotions — vulnerability, grief, fear of rejection, the sting of being seen as needy — joy can't get in either. Emotions don't work like a buffet where you can pick the pleasant ones and leave the rest. They travel together. And when you block the ones that feel dangerous (like the ones that come up when you ask for help), you also block the ones you're desperately missing.

This is what Hudson calls the Golden Algorithm in action. When you avoid vulnerability, you don't get less of the painful emotions — you get more of them, just in a different form. The loneliness. The resentment. The bone-deep exhaustion of carrying everything alone. The flat, gray feeling of going through the motions while wondering when life started feeling so... small.

Are you stuck in a “transactional help only” rut?. Maybe you're reading this thinking, "I actually do ask for help." And you do — as long as it's transactional. You'll hire the organizer, pay the therapist, Venmo the babysitter, immediately reciprocate when a friend does you a favor. Help that's paid for or immediately bartered feels fine. Tit for tat. Slate wiped clean. Nobody owes anyone anything.

But what about leaning on a friendship in a way that's a little lopsided for a while? No promise to repay immediately. No grand thank-you gesture to zero out the balance sheet. Just trusting that they'll ask for your help when they need it and it'll all work out. What's uncomfortable for you in that? Because it's usually an untapped goldmine.

The emotional experience most of us are avoiding in that scenario is indebtedness. Or more precisely, the vulnerability of being someone who needed something and can't immediately earn back their standing. When you keep all help transactional, you stay in control. You're the competent person who hired a service. You're the thoughtful friend who brought wine to say thanks. You never have to sit in the squirmy discomfort of just... receiving. Of being a person who took more than they gave for a minute, and trusting that the relationship can hold that.

But that squirmy discomfort? That's where the real connection lives. Friendships deepen not through tidy exchanges but through the messy, imperfect, sometimes-lopsided reality of people showing up for each other. When you let someone help you without immediately settling the score, you give them something too — the experience of being needed, trusted, and close to you. And that closeness is what most of us are actually hungry for underneath all the competence.

And on the other side — this is the part I want to be specific about, because I think it's easy to talk about "emotional freedom" in abstract terms that don't land for someone in the middle of burnout — on the other side of learning to ask for and organize support, something shifts that's hard to describe until you've felt it.

It feels like breathing deeper than you have in years. Like a physical loosening in your chest and shoulders that you didn't know was there because you'd been holding it so long.

It feels like being surprised. Someone handles something and it goes fine — maybe even better than fine — and you realize you'd been bracing for catastrophe that never came.

It feels like being known. Not as the competent one, the together one, the one who doesn't need anything. But as a full person with rough edges and real needs who is still, somehow, wanted. That's the sweetness I'm talking about. Being loved not despite your needs but with them visible.

It feels like having more to give. This one catches people off guard. They expect that accepting help will make them feel diminished. Instead, they have more energy, more patience, more humor. They're better partners, better parents, better leaders. Because they're not running on fumes.

I know those descriptions sound intangible. And I know that when you're in the middle of carrying everything, the idea that asking for help could lead to any of that feels impossibly far away. The gap between where you are and that kind of ease feels like a canyon. But in my experience, both personally and with clients, the bridge across that canyon isn't built in one heroic leap. It's built in tiny, annoying, uncomfortable increments.

Which brings us to the practical part.

Four Ways to Start Asking Before DEFCON 1

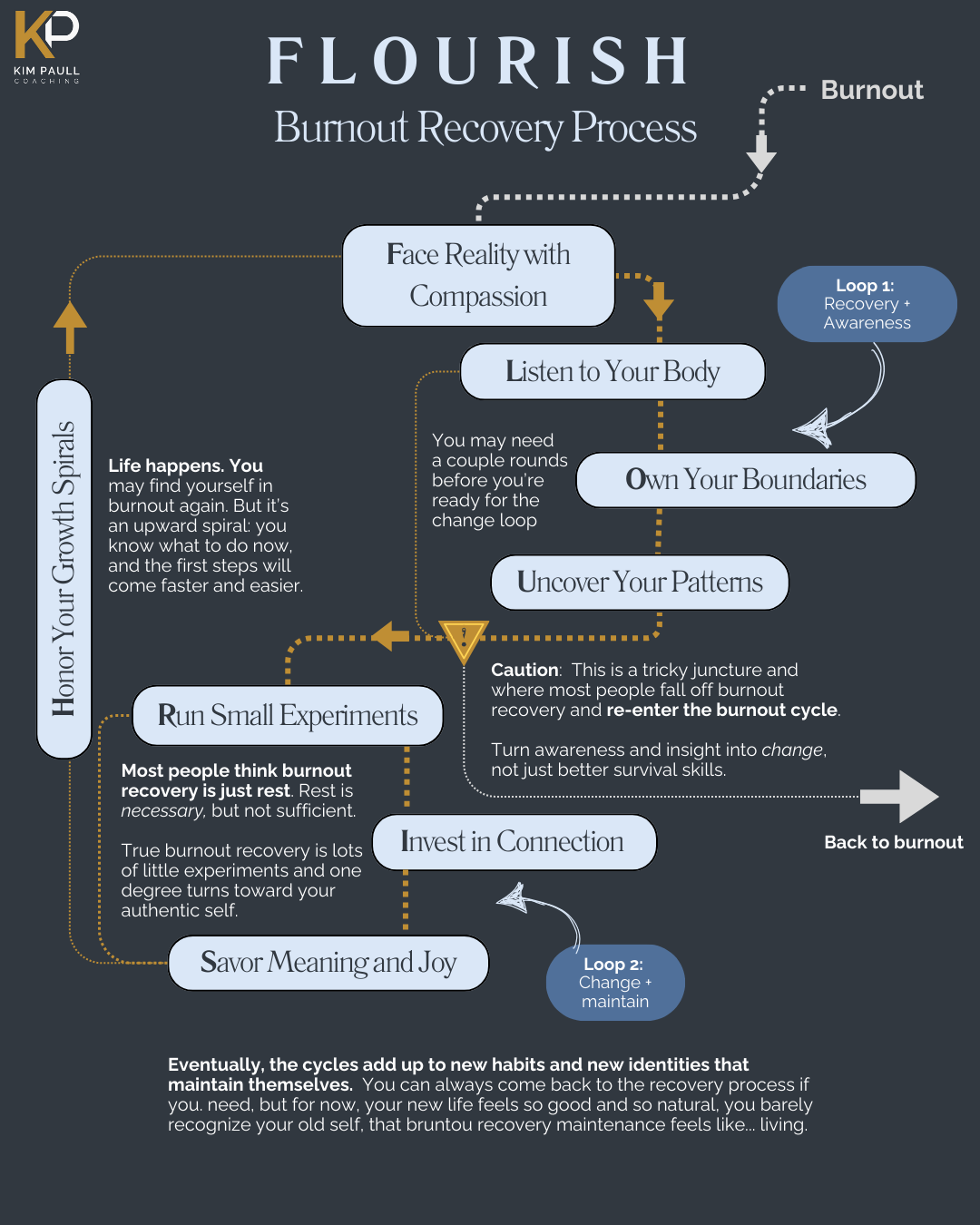

These aren't homework. They're not another checklist. Think of them more as experiments — tiny, low-stakes ways to practice something your nervous system might resist. In my FLOURISH burnout recovery process, I call this "running small experiments," because the word "experiment" takes the pressure off. You're not committing to a permanent change. You're trying something and seeing what happens.

1. Notice where you're overfunctioning AND underfunctioning at the same time

This one surprises people, but it's almost always true. The areas where you're carrying too much are directly connected to the areas you've quietly dropped.

Maybe you're managing every detail of your kids' schedules but you haven't called your best friend in two months. Maybe you're crushing it at work but your joints hurt and your sleep is terrible. Maybe you're running the household like a military operation but you can't remember the last time you did something purely for fun.

The underfunctioning isn't laziness. It's the natural result of a finite human being trying to carry an infinite load. Your capacity has to come from somewhere.

Try this — just as an observation, not as a judgment. Write down where you're carrying the most. Then look at what's dropped. Not to feel bad about it. Just to see the tradeoff clearly. Sometimes just seeing the cost makes it easier to consider doing something different.

2. Borrow a little DBT — try Opposite Action

Dialectical Behavior Therapy, developed by psychologist Marsha Linehan, has a skill called "Opposite Action" that's surprisingly useful here. The basic idea is this — when an emotion is driving a behavior that isn't serving you, try doing the opposite of what the emotion urges you to do.

When you feel the urge to handle something alone, the opposite action would be to tell someone — even if it's small, even if it feels unnecessary, even if the voice in your head says "this isn't a big enough deal to bother anyone with."

The key from DBT is that you don't have to wait until you feel like asking for help to do it. Sometimes the feeling follows the action, not the other way around.

Some very low-stakes experiments to try.

At home, when your partner asks "What can I do?", instead of saying "Nothing, I've got it," try answering with one specific, concrete thing. "Can you switch the laundry?" Even if it feels weird. Even if they do it wrong. And then — this is the critical part — leave the room. Give them the space to actually do it without your oversight.

At work, next time you're in a 1:1 with your manager and something is weighing on you, say it out loud. Not as a complaint. Just information. "I want to flag that the timeline on this project is tighter than I initially estimated, and here's what I'm thinking about how to address it."

In a friendship, text someone back and say the honest thing instead of the curated version. "I've been really tired and kind of struggling and I want to hang out but I don't have the bandwidth to plan anything. Can you pick the place and time?"

None of these take more than five minutes. And each one interrupts the pattern by just a tiny degree.

3. Use "and" instead of "but" to soften the story

Another DBT concept that's incredibly practical for this: dialectical thinking. It's the practice of holding two seemingly opposite truths at the same time, connected by "and" instead of "but."

Notice how your inner dialogue sounds when you think about asking for help.

"I should be able to handle this BUT I can't" becomes "I'm capable AND I need support right now."

"Other people have it worse BUT I'm overwhelmed" becomes "Other people are struggling AND so am I, and both are real."

"I want help BUT I'm afraid of being a burden" becomes "I want help AND I'm noticing fear about being a burden. Both are here."

The shift from "but" to "and" doesn't make the hard part disappear. It just stops making you fight yourself. It lets both things be true. And in my experience, that's when people start to move.

4. Prepare for the internal resistance — and welcome it in

This might be the most important one. When you start experimenting with asking for help, expect to hear from some familiar internal voices. The guilt tripper. The perfectionist. The people pleaser. The catastrophist. The voice that tells you you're selfish, lazy, a mess.

Internal Family Systems would call these "parts," and they're not enemies — they're protectors that have been working overtime. They took on these roles because, at some point, that's what you needed to survive.

Joe Hudson puts this beautifully in his framework — if you can't welcome the emotion itself, welcome the resistance. Put your attention on the part of you that's resisting. Be in wonder, not judgment. Allow it to express itself without rushing to change it. Be with the resistance the way you'd sit with a scared child — patiently, lovingly, without pushing it to "not" be resistant. (Art of Accomplishment — "How to Feel Your Emotions")

So when the guilt shows up after you let your partner handle bedtime alone, or when the perfectionism flares because the babysitter folded the towels wrong, or when you suddenly feel an urgent need to reorganize the pantry instead of sitting with the discomfort of having less to do — notice it. Name it if you can. And try something like: "Hey, I see you. I know this is new and uncomfortable. We can always go back to the old way if we need to. But let's try this first."

One thing I'll flag from my own experience and from watching dozens of clients navigate this: sometimes when you start letting go of control in one area, your brain will redirect the anxiety into another area entirely. Maybe your world-event anxiety spikes, or you suddenly become very interested in calorie counting, or your body image stuff peaks. That's expected. It's your system looking for a new place to channel the discomfort. Expect it. Welcome it. And tell it you're just trying something new.

A Little About How I Got Here (And How I'm Getting Out)

I'll spare you the full autobiography, but the highlights are relevant.

When my twins were newborns and people showed up to help, I entertained them. I made chit chat (which I genuinely love, to be fair — I just had no brain left). I told people we were fine because... I thought I was? I didn't know what "not fine" felt like until it became epic.

Which is why I finally entered therapy when the babies were 18 months old and I was consumed with body dysmorphia. Turns out, I was just channeling all my difficulty with vulnerability and asking for support into beating myself up, because that felt more certain. More controllable. Within three sessions, both my therapist and I could see that body image wasn't actually the problem. It was just the loudest symptom.

It's been a long journey since. I have become a literal burnout prevention professional — for myself, mostly. You all just get the runoff.

I hated that place of emotional exhaustion, apathy, loneliness while never actually being alone, cynicism. Telling myself "why bother?" and "this is just life now." Hyperfixating on arcane nutrition facts and macro counting as a distraction from the real issue.

Those stories my brain was creating weren't random. They were self-soothing. Because what the brain hates more than internal bullying is uncertainty — the possibility that someone might think you're lazy, incapable, disorganized, not uniquely strong and resilient. The inner bully at least gives you something to do about it. It's a terrible solution, but it's a solution.

Hudson's Joy quote haunts me here. For years, I was trying to feel peace, connection, ease — while systematically shutting the door on the emotions that were prerequisites for those things. You can't get to joy by going around grief, vulnerability, and the genuine discomfort of needing other people. You have to go through them. And going through them requires letting someone see you in the middle of it.

I'm not "recovered." I'm in recovery. Life is calmer now. I started small — and that's what I want to offer you.

There’s More, if You Want to Go Deeper

Everything I've described above works. Small experiments, opposite action, dialectical thinking, noticing the internal resistance — these are real, evidence-based tools. They can help you start asking for help sooner and carrying less alone.

But.

If you find yourself reading this and thinking "I know what I should do but I still can't make myself do it" — that's actually the most important piece of information here.

Because the tools only go so far when the underlying belief is still running the show. If somewhere deep down, you believe that your worth comes from how much you carry, how self-sufficient you are, how unreproachable your effort is — you'll find a way to recreate the overfunctioning pattern in whatever new system you build. You'll optimize the calendar, hire the babysitter, delegate at work, and still feel exhausted. Because the doing changed but the belief didn't.

This is what I call the "Wind" in the Forest Fire Model — the thing that fans the flames even after you've changed the external conditions. Hyper-empathy, people-pleasing, conflict avoidance, the fierce inner critic that measures your worth by your output. These don't quiet down because you downloaded a better task management app.

And Hudson's Golden Algorithm helps explain why. When you avoid the emotional experience of being truly seen — with your mess visible, your needs out in the open, your competence temporarily suspended — you don't escape the pain. You just redistribute it. Into resentment. Into exhaustion. Into that flat, gray feeling of going through the motions. The emotions you're avoiding come back in exactly the form you were trying to prevent.

The way out isn't more strategies for asking for help. The way out is developing the capacity to feel what comes up when you do. The vulnerability. The grief of realizing how long you've been alone with this. The fear that people will see you differently.

And — maybe the hardest one — the strange, almost unbearable sweetness of being genuinely supported.

That last one surprises people. But I see it all the time. Clients who can handle any crisis but fall apart when someone shows up for them with real care and zero agenda. Because receiving is its own form of vulnerability. And for some of us, it's the scariest one.

It's also worth naming something uncomfortable: if you struggle with asking for help, you're probably going to struggle with asking for help with asking for help. That's the nature of this cycle. The very skill you need to develop — reaching out, being vulnerable, admitting you can't do it alone — is the skill you've spent your whole life avoiding.

I know because I lived in that cycle for years. My body was telling me. My relationships were telling me. My brain fog, my snapping at my kids, my 3 a.m. wake-ups — all telling me. And I still thought the answer was a better morning routine.

The answer wasn't a routine. It was relationships — with a therapist, with authors and teachers and people who'd been down this road before me, with my village, my network, my community. And eventually, with the parts of myself I'd been shoving underwater for decades.

And here's the thing I didn't expect. Asking for help didn't just lighten the load. It made me less lonely. Because people want to help. They want to close the loop, solve the problem, be useful. And when you let them, they feel closer to you afterward. And you want to do the same for them. It creates this cycle of reciprocity and warmth that I'd been starving for while simultaneously refusing to let anyone feed me.

In my FLOURISH framework, the first step is "Face Reality with Compassion." Not face reality with a new productivity system. Not face reality and immediately fix everything. Face it, and be kind to yourself about what you see. Because the patterns that got you here made sense. They kept you safe, capable, irreplaceable. And they're now costing you more than you want to pay. Both things are true.

My FLOURISH Burnout Recovery methodology — Step 1, Facing Reality with Compassion

If This Hits

A blog post can start a conversation, but it can't hold the whole thing.

What I've described here — mapping your burnout, understanding the beliefs underneath the overfunctioning, recognizing how you've unintentionally trained people not to help, developing the capacity to receive support without white-knuckling through guilt, building back your energy and agency one small experiment at a time — that's the work we do in coaching.

If you're curious about what that looks like, I have a few options depending on where you are:

Regenerate + Relaunch is my 13-session burnout recovery experience — the full FLOURISH framework, customized to your burnout map, your patterns, your life.

Speaking + Training — if you're a leader or organization wanting to bring this work to your team, I'd love to talk about what that could look like.

And if you know someone who needs to read this — the friend who shows up looking completely put-together and never asks for a single thing — please send it her way. My referral program is my way of saying thank you for helping this work reach the people who need it, because burnout recovery is contagious in the best possible way.

You don't have to be in emergency mode to deserve support. You don't have to have the car-detailer-texting-his-colleague moment before you're "bad enough" to ask. The whole point is to get ahead of DEFCON 1 — even by a little. Even by one text. Even by one honest sentence.

You've been handling everything for a long time. And that took guts. But so does this.

I'm here if you want to talk about it.

For more on burnout recovery, the FLOURISH framework, and tools for building a life that doesn't require emergency-level functioning, visit the Quitters Club blog or the Resources page. And for stories, science, and the occasional rant, listen to the Now That You See It podcast.