The Burnout-Proof Body: How to Eat and Move According to Your Stress Level

In a world that glorifies hustle culture, understanding when to push and when to pause might be your most powerful performance tool.

Introduction: When Your Body Keeps Score

I'm so excited to write this post because I've made ALL the mistakes. And I mean ALL of them.

As a former all-round athlete with an intense streak of manic training, I've been there. Soccer, basketball, and then years of rowing—sometimes up to 3 times a day. Half marathon training. The hardest HIIT workouts only. The most reps. Supersetting everything because "rest is wasted training time." So much diet and body control and cognitive depletion from the tracking and rumination.

But here's what I didn't realize: all of that "healthy" behavior was actually driving me deeper into burnout. I had no idea.

And I guarantee you there are "bro trainers" out there telling women that the best way to "lose weight" and get in shape is to cut calories and pump up the high-intensity body pump HIIT workouts. Not only doesn't that work over the long haul (after you get some newbie crash gains and then hit a painful plateau anyway), but it can dig you deeper into burnout. And what happens then? You just keep working out harder and cutting more calories in a desperate attempt to see results.

I'm excited to write this post because there are so many people out there like me who don't know that the way they think they're taking care of themselves—preventing burnout even!—is actually driving them deeper in.

Here's the reality: You have a presentation due tomorrow, your child woke up with a fever, your basement flooded last week, and you're trying to cut back on sugar because your doctor mentioned your blood work wasn't ideal. To your conscious mind, these are separate challenges. To your nervous system, they're all simply "threats" requiring the same biological response.

What if I told you that the way you eat and move could either amplify or soothe this stress response? And that customizing your approach based on your current burnout level could be the difference between breakdown and breakthrough? As I explore in my Quitter's Club Blog, quitting the burnout cycle often means adopting a completely different approach to how we care for our bodies.

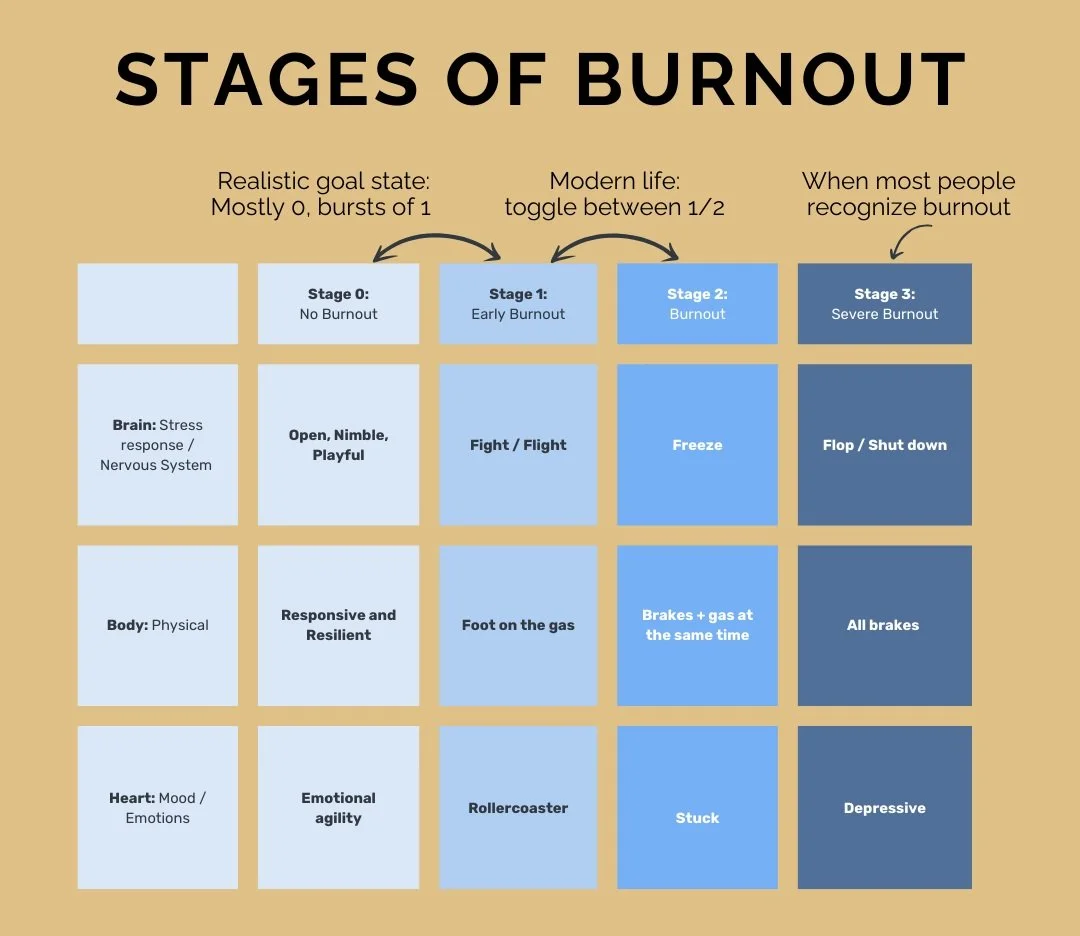

Burnout isn't just feeling tired or overwhelmed—it's a physiological state with measurable impacts on your hormones, immune system, and metabolic health. Understanding where you fall on the burnout spectrum can help you align your nutrition and movement practices with what your body actually needs, not what social media or even outdated research suggests you "should" be doing.

This guide will help you identify your current burnout stage based on how your nervous system is responding and provide specific, evidence-based recommendations for nutrition and movement that support—rather than sabotage—your recovery and performance.Burnout Stages and their Nutrition and Movement Support at a Glance: Your Quick Reference Guide

| Burnout Stage | Key Characteristics | Nutrition Approach | Movement Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0: Well-Regulated | • Balanced energy • Good sleep • Handles challenges well • Emotionally regulated |

• Regular protein-rich meals • Strategic carb timing • Nutritional variety • Metabolic flexibility |

• Progressive strength training • Structured intensity • Skill development • Planned recovery periods |

| Stage 1: "All Gas" | • Wired but tired • Racing thoughts • Trouble sleeping • Constant urgency |

• Regular meals (3-4 hrs) • Increased carbohydrates • Magnesium-rich foods • Limited caffeine |

• Reduced workout volume • Strength over cardio • Walking as primary cardio • More recovery days |

| Stage 2: "Gas & Brakes" | • Brain fog • Overwhelm • Digestive issues • Emotional numbness |

• Easy-to-digest foods • Anti-inflammatory focus • Warm, cooked meals • Blood sugar stability |

• Gentle, tension-releasing movement • Nature walking • Restorative yoga • Brief movement "snacks" |

| Stage 3: "All Brakes, or Shutdown" | • Deep fatigue • Apathy • Weak immunity • Possible depression |

• Small, frequent meals • Easily digested proteins • Eliminate all food stressors • Nutrient-dense focus |

• Minimal movement only • 5-15 minute sessions • Recumbent or water-based movement • Multiple rest days between any activity |

Understanding Burnout Through Your Nervous System

To understand burnout, we need to understand how your nervous system responds to stress. Rather than getting technical with complex theory, let's use a simple car metaphor that I often discuss in my burnout recovery coaching:

Stage 0: Well-Regulated (Balanced)

Nervous System State: This is your body's balanced state, where you have access to both activity when needed and rest when appropriate.

How It Feels: You wake up refreshed, handle challenges with perspective, connect easily with others, and have stable energy throughout the day. Your digestion works well, and you can transition between focus and relaxation without struggle.

Stage 1: "All Gas" (Sympathetic Activation)

Nervous System State: This is like having your foot stuck on the accelerator. Your body is pumping stress hormones, preparing you for action.

How It Feels: You're wired but tired—buzzing with nervous energy, having trouble sleeping despite exhaustion, experiencing racing thoughts, and feeling a constant sense of urgency. You might be productive in short bursts but struggle to sustain focus.

Stage 2: "Gas and Brakes Simultaneously" (Mixed State)

Nervous System State: Your body is trying to both activate and shut down at the same time—creating an internal tug-of-war.

How It Feels: You experience brain fog, indecision, emotional numbness or irritability, digestive issues, and a profound sense of overwhelm. You might find yourself staring at your computer screen unable to start tasks or feeling "stuck" despite having important deadlines.

Stage 3: "Shutdown" (Conservation Mode)

Nervous System State: Your body has flipped into an energy conservation mode, reducing all non-essential functions.

How It Feels: Deep fatigue that sleep doesn't fix, apathy, disconnection from others, possible depression, weakened immune function, and loss of motivation even for activities you used to enjoy. This state often follows prolonged periods in Stages 1 and 2 without adequate recovery.

Food Sensitivities: The Hidden Stress Multiplier

When exploring burnout recovery in my wellness coaching practice, I often find that unidentified food sensitivities can be a significant, invisible stress factor for many people. Your body doesn't distinguish between different types of stress, and an immune reaction to food can trigger the same stress response as a work deadline or relationship conflict.

How Food Sensitivities Contribute to Burnout

Food sensitivities differ from true allergies (which cause immediate, sometimes life-threatening reactions) and work through different mechanisms:

Chronic Inflammation: Repeatedly consuming trigger foods can create low-grade, systemic inflammation that taxes your immune system and stress response

Gut-Brain Connection: Food sensitivities often compromise gut integrity, which directly affects mood, energy, and cognitive function through the gut-brain axis

Stress Hormone Activation: Your body treats food sensitivities as a form of stress, potentially increasing cortisol and contributing to burnout

Nutrient Absorption Issues: Sensitizing foods can damage the gut lining, reducing your ability to absorb nutrients needed for energy production and stress recovery

Common Signs of Food Sensitivities

Unlike allergies, sensitivities can be subtle and difficult to connect with specific foods. Signs include:

Fatigue after meals

Brain fog or difficulty concentrating

Headaches or migraines

Joint pain or muscle aches

Skin issues (eczema, rashes, acne)

Digestive symptoms (bloating, gas, constipation, diarrhea)

Mood changes, anxiety, or irritability

Congestion or post-nasal drip

Dark circles under eyes

Water retention

Sleep disturbances

Identifying Your Trigger Foods

There are several approaches to identifying food sensitivities:

Food and Symptom Journaling: The simplest starting point is to track everything you eat and any symptoms you experience. Look for patterns that emerge over 2-3 weeks.

Elimination Diet: This involves removing common trigger foods (gluten, dairy, soy, corn, eggs, nuts, nightshades) for 3-4 weeks, then systematically reintroducing them one at a time while monitoring for reactions. This approach takes commitment but is considered the gold standard.

Modified Elimination: If a full elimination feels overwhelming, try removing just the top two suspects (commonly gluten and dairy) for two weeks, then reintroduce them separately.

Laboratory Testing: Various tests are available, though none are perfect:

IgG food sensitivity testing (blood test)

ALCAT or MRT testing (measures cellular reactions to foods)

Intestinal permeability testing (indicates whether you have "leaky gut" that may contribute to sensitivities)

Addressing Sensitivities in Different Burnout Stages

How you approach potential food sensitivities should match your current burnout level:

Stage 0 (Well-Regulated): This is the ideal time to conduct a methodical elimination diet as you have the energy and cognitive resources to follow through.

Stage 1 ("All Gas"): Consider testing rather than elimination protocols, as adding dietary restriction during sympathetic activation can increase stress. Focus on adding anti-inflammatory foods rather than just removing triggers.

Stage 2 ("Gas & Brakes"): Start with removing the top two most common triggers (gluten and dairy) while emphasizing easy digestion and blood sugar stability.

Stage 3 ("Shutdown"): Work with a healthcare provider to identify the gentlest approach. Often, focusing on a simple, whole-foods diet with minimal processing is the place to start before attempting more restrictive protocols.

Remember that removing sensitizing foods isn't about restriction—it's about reducing an invisible stressor that may be keeping your nervous system on high alert even when you're doing everything else "right."

Your Stress Response: When Your Body's Alarm System Gets Stuck

When we experience stress, our body activates a stress response system that releases hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. In my stress management resources, I often explain that this is like your body's alarm system—helpful when there's an actual emergency, but problematic when it won't turn off.

Problems arise when this system stays activated too long without adequate recovery periods. Research shows that chronic stress hormone activation leads to dysregulation in cortisol production, which is strongly associated with burnout symptoms.

With prolonged stress, your body's alarm system essentially breaks—either staying on all the time or becoming erratic. The effects are very real:

Disrupted daily energy patterns (fatigue when you should be alert, wired when you should be sleepy)

Inflammatory responses throughout the body

Metabolic changes that affect weight and energy use

Compromised immune function (getting sick more often)

Digestive disturbances (IBS, acid reflux, etc.)

Changes in menstrual cycles and other hormone functions

This matters tremendously for how we eat and move because both food choices and exercise can either help repair this system or further damage it.

The Exercise Paradox: When Movement Helps vs. When It Harms

Exercise is one of our most powerful tools for stress management. Research consistently shows that regular physical activity reduces anxiety, improves mood, and enhances cognitive function. According to Emily and Amelia Nagoski, authors of Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle, movement is one of the most effective ways to complete the stress cycle—helping our bodies process and release tension rather than storing it.

However, exercise is also, by definition, a stressor.

When we work out—particularly with high-intensity training—we create mechanical strain on muscles, generate oxidative stress, elevate core temperature, and trigger an inflammatory response. In a well-rested, well-nourished body, these stressors stimulate positive adaptations: stronger muscles, improved cardiovascular capacity, enhanced metabolic health.

But when our stress bucket is already overflowing from work pressure, relationship challenges, financial concerns, or inadequate sleep, adding intense exercise can push us deeper into burnout rather than relieving it. This is something I discuss in detail in my exercise for busy professionals resource guide.

Dr. Peter Attia has spoken extensively about the "hormetic zone" for exercise—the sweet spot where the stress of training stimulates positive adaptations without overwhelming recovery capacity. This zone shifts depending on your overall stress load and burnout stage.

When Exercise Becomes Another Form of Control

For high-achievers prone to burnout, exercise can sometimes become problematic in another way: as a control mechanism.

When other aspects of life feel chaotic—perhaps you're dealing with a challenging work transition, family illness, or financial uncertainty—the measurable, controllable nature of exercise can become appealing. "I can't fix my toxic work environment today, but I can complete this workout." This isn't inherently negative, but it becomes problematic when:

Exercise serves to mask deeper issues that need addressing

Exercise intensity doesn't match your current recovery capacity

The exercise becomes compulsive rather than supportive

This tendency toward using exercise as control is often intertwined with similar patterns around food, which we'll explore further when discussing orthorexia.

Female Physiology: How Women Experience Stress Differently

Female bodies respond to stress in ways that differ significantly from male bodies, largely due to hormonal influences and cyclical patterns. Understanding these differences is essential for women seeking to optimize their approach to nutrition and movement during high-stress periods.

The Female Stress Response: More Nuanced Than Fight-or-Flight

While the traditional "fight-or-flight" model of stress response has dominated research for decades, more recent studies suggest that women often exhibit a "tend-and-befriend" response to stress. This pattern, first identified by UCLA researcher Dr. Shelley Taylor, involves nurturing behaviors (tending) and seeking social connection (befriending) under stress.

This difference is partly mediated by oxytocin, which is released during stress in both men and women but appears to have stronger behavioral effects in female bodies due to its interaction with estrogen. While this can be a strength—women often maintain stronger social supports during stress—it can also mean women absorb others' stress more readily, particularly if they're in caregiving roles.

Hormonal Cycles: A Monthly Stress Barometer

For menstruating women, the menstrual cycle serves as a sensitive indicator of stress levels. The hypothalamus, which helps regulate both stress responses and reproductive hormones, often prioritizes stress management over reproductive function when resources are limited.

Dr. Cynthia Thurlow has discussed how stress can manifest as:

Irregular cycles

More painful periods

PMS intensification

Shorter luteal phases

Heavier or lighter bleeding

Missed periods entirely

What's fascinating is that these changes aren't just inconveniences—they're meaningful data about your overall stress load and recovery status. On my women's wellness blog, I often emphasize how tracking cycle changes can provide early warning signs of burnout.

Perimenopause: When Stress Sensitivity Increases

Women in perimenopause (typically starting in their 40s) face unique challenges when it comes to stress management. As Dr. Becky Campbell explains, declining progesterone levels can make perimenopausal women more sensitive to stress, as progesterone has natural calming, anti-anxiety effects on the brain.

This creates a challenging feedback loop: stress depletes progesterone, which makes you more sensitive to stress, which further depletes progesterone.

For women in this stage of life, especially gentle nutrition and movement approaches may be necessary during high-stress periods. Dr. Gabrielle Lyon emphasizes the importance of protein intake during perimenopause to maintain muscle mass, which becomes increasingly important for metabolic health as estrogen levels decline.

Luteal Phase: The Critical Recovery Window

The luteal phase (post-ovulation until menstruation) represents a crucial recovery window in a woman's cycle. During this phase:

Energy needs naturally increase (by 100-300 calories per day)

The body is more sensitive to blood sugar fluctuations

Recovery from exercise takes longer

Sleep quality may be compromised

Unfortunately, many women do the opposite of what their bodies need during this phase—restricting calories when their bodies need more fuel and pushing through intense workouts when their recovery is already compromised.

Research indicates that respecting this natural cycle—eating more during the luteal phase and focusing on recovery-based movement—supports hormonal health and may help prevent burnout in the long term.

Nutrition Approaches Across the Burnout Spectrum

Let's explore how nutrition needs shift as we move through different burnout stages. Remember: the goal isn't perfection but alignment with your body's current capacities and needs.

Stage 0 Nutrition: Optimizing Performance (No Burnout)

When your nervous system is regulated and stress levels are manageable, your body can handle more nutritional variety and occasional challenges.

Key Principles:

Adequate Protein: Dr. Gabrielle Lyon recommends 30-40g protein per meal for most active adults to support muscle protein synthesis

Carbohydrate Timing: Strategic carbohydrate intake around workouts to support performance and recovery

Caloric Sufficiency: Eating enough to support activity levels and recovery

Nutrient Density: Focus on whole foods that provide micronutrients needed for cellular energy production

Metabolic Flexibility: Occasional fasting or carbohydrate manipulation may be well-tolerated

What This Looks Like:

Planned meal timing around workouts

Performance-focused approach

Occasional nutritional challenges (like time-restricted eating) if desired

Room for social eating and treats without significant impact

Research Perspective: A 2022 review in Sports Medicine found that individuals with low allostatic load (a measure of cumulative stress) showed better adaptations to various nutritional strategies than those with higher stress markers (Heaton et al., 2022).

Stage 1 Nutrition: Supporting the Stress Response (Sympathetic Activation)

When your sympathetic nervous system is chronically activated, nutrition approaches need to focus on stabilizing blood sugar and supporting the increased metabolic demands of the stress response.

Key Principles:

Blood Sugar Regulation: More frequent meals to prevent cortisol spikes from hypoglycemia

Increased Antioxidants: Combat the oxidative stress that accompanies sympathetic activation

Magnesium-Rich Foods: Support nervous system regulation (dark chocolate, nuts, seeds, leafy greens)

Adequate Carbohydrates: Particularly important as prolonged sympathetic activation increases carbohydrate utilization

Hydration: Stress increases fluid needs

What This Looks Like:

Regular meals every 3-4 hours

Protein + fiber + healthy fat at each meal

Emphasis on cooked foods that are easier to digest

Mindful caffeine intake (typically before 12pm only)

Avoidance of extensive fasting

Research Perspective: Studies have shown that prolonged sympathetic activation increases reactive oxygen species production, suggesting a higher need for antioxidant-rich foods during periods of elevated stress (Aschbacher et al., 2013).

Stage 2 Nutrition: Calming the System (Functional Freeze)

When caught in the "gas and brakes simultaneously" phase, nutrition should prioritize nervous system regulation and digestive support.

Key Principles:

Digestive Ease: Focus on easily digestible foods as digestive function is often compromised

Anti-Inflammatory Emphasis: Reduce additional inflammation from food triggers

Parasympathetic Support: Warm, cooked foods and mindful eating practices

Elimination of Additional Stressors: Typically not the time for restrictive diets or nutritional experiments

Blood Sugar Stability: Critical for preventing additional stress hormone surges

What This Looks Like:

Warm, cooked meals rather than raw foods or cold smoothies

Soups, stews, and slow-cooked meals

Fermented foods for gut health (if well-tolerated)

Mindful eating practices (sitting down, no screens, conscious chewing)

Potentially eliminating common inflammatory triggers temporarily (gluten, dairy, alcohol, excess sugar)

Research Perspective: The connection between gut health and stress is bidirectional—chronic stress alters gut function, and gut dysfunction can exacerbate stress responses, creating a vicious cycle that may contribute to functional freeze states (Madison & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2019).

Stage 3 Nutrition: Nourishing Recovery (Dorsal Vagal Collapse)

In the shutdown phase, nutrition becomes about gentle nourishment and rebuilding physiological reserves.

Key Principles:

Micronutrient Density: Focus on nutrient-rich foods to address likely deficiencies

Consistent Blood Sugar: Small, frequent meals to prevent additional stress on the system

Easily Absorbed Nutrients: Accounting for likely digestive impairment

Elimination of All Unnecessary Food Stressors: Including both inflammatory foods and difficult eating patterns

Caloric Sufficiency: Absolutely not the time for caloric restriction

What This Looks Like:

Small, frequent meals centered around easily digested proteins

Bone broth and other glycine-rich foods to support healing

Cooked vegetables rather than raw

Potential temporary supplements to address deficiencies (under healthcare supervision)

Complete elimination of alcohol, excessive caffeine, and processed foods

Research Perspective: Studies on recovery from chronic fatigue syndrome (which shares features with Stage 3 burnout) indicate that micronutrient status—particularly B vitamins, magnesium, and Vitamin D—plays a crucial role in energy production and recovery potential (Bjørklund et al., 2019).

Movement Strategies Across the Burnout Spectrum

Just as with nutrition, the optimal approach to movement varies dramatically based on your current burnout stage. The goal is to use movement as medicine, not as another source of stress your body can't process.

Stage 0 Movement: Performance Focus (No Burnout)

When your nervous system is well-regulated and recovery capacity strong, you can tolerate and benefit from more challenging exercise.

Key Principles:

Progressive Overload: Systematically increasing training demands for continued adaptation

Structured Intensity: Including appropriate high-intensity work

Planned Recovery: Intentional rest days and deload weeks

Movement Variety: Incorporating strength, cardiovascular fitness, flexibility, and skill development

Performance Metrics: Tracking progress through measurable outcomes

What This Looks Like:

Structured resistance training 3-5 times weekly

Strategic cardiovascular training based on goals

Occasional higher-intensity sessions

At least one full rest day weekly

Planned deload weeks every 4-8 weeks

Expert Perspective: Peter Attia emphasizes that even at peak fitness, planned recovery is non-negotiable: "Even elite athletes spend more time recovering than training. The performance comes from the adaptation to the training, not the training itself."

Stage 1 Movement: Stress-Appropriate Training (Sympathetic Activation)

When your sympathetic nervous system is already highly activated, movement needs to be carefully calibrated to avoid pushing you further into burnout.

Key Principles:

Lower Training Volume: Reduced overall exercise load

Emphasis on Resistance: Strength training provides better stress-adaptation than high-intensity cardio

Heart Rate Monitoring: Keeping cardiovascular work below individual thresholds

Increased Recovery: More rest days between challenging sessions

Breath-Focused Components: Incorporating parasympathetic activation

What This Looks Like:

Resistance training 2-3 times weekly with longer rest periods

Walking as primary cardio

Zone 2 cardio (conversational pace) if more endurance work is desired

Yoga or breath-focused movement on recovery days

More rest days between intense sessions

Research Perspective: Studies show that excessive high-intensity training during periods of high life stress can compound sympathetic activation and impair recovery, particularly affecting sleep quality and resting heart rate variability (Hynynen et al., 2011).

Stage 2 Movement: Restorative Practices (Functional Freeze)

When caught in the tug-of-war of functional freeze, movement should help discharge tension and activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

Key Principles:

Tension Release: Practices that help discharge stored stress energy

Nervous System Regulation: Movement that activates the parasympathetic response

Mindful Engagement: Connecting movement with breath and sensation

Nature Exposure: Outdoor movement when possible

Joint Mobility: Gentle movement to address the effects of freeze physiology

What This Looks Like:

Walking in nature

Gentle yoga with emphasis on embodiment rather than achievement

Tai chi or qigong

Light resistance training with emphasis on form and breath

Dance or intuitive movement that feels pleasurable

Expert Perspective: Cait Donovan and Sarah Vossen discuss on the Fried Podcast how "completing the stress cycle" through movement can help discharge the energy locked in the body during functional freeze states, even when the original stressors persist.

Stage 3 Movement: Minimal Effective Dose (Dorsal Vagal Collapse)

In the shutdown phase, even gentle movement may feel overwhelming. The focus becomes the minimal effective dose to maintain function while prioritizing recovery.

Key Principles:

Non-Negotiable Recovery: Rest is the primary "workout"

Minimal Movement Threshold: Just enough to maintain basic function

Parasympathetic Activation: Movement that supports nervous system regulation

Pleasure-Based: Following genuine body cues rather than external prescriptions

Progressive Re-Integration: Gradual return to more active movement as capacity rebuilds

What This Looks Like:

Gentle walking for 5-15 minutes

Restorative yoga (primarily floor-based with support)

Basic mobility work while lying down

Breathing practices with minimal movement

Recumbent movement (swimming can be ideal if available)

Research Perspective: Studies on chronic fatigue syndrome suggest that graded exercise therapy should be extremely conservative, beginning at levels that may seem trivial and progressing very gradually to prevent setbacks (Davenport et al., 2010).

The Control Paradox: When Healthy Habits Become Harmful

For high-achievers prone to burnout, seemingly "healthy" behaviors around food and exercise can sometimes become problematic control mechanisms that actually perpetuate burnout. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for sustainable wellbeing.

The Psychological Appeal of Control

When life feels chaotic—perhaps you're dealing with workplace uncertainty, relationship challenges, or financial strain—the measurable, controllable aspects of nutrition and fitness can become powerfully appealing.

"I can't fix my toxic work environment today, but I can stick to my meal plan." "I can't control my child's health challenges, but I can control my workout schedule."

In moderation, finding areas where you can exercise agency is healthy. Problems arise when:

These behaviors mask deeper issues that need addressing

The control mechanisms themselves become additional stressors

The rigidity of these behaviors prevents adapting to your body's changing needs

I've written about this extensively in my perfectionism and burnout series, where I explore how our attempts to control can sometimes backfire.

Orthorexia: When "Healthy Eating" Becomes Unhealthy

Orthorexia nervosa describes an unhealthy fixation on "proper" eating. Unlike other eating disorders primarily focused on quantity, orthorexia centers on food quality and purity. Warning signs include:

Compulsive checking of ingredient lists and nutritional labels

Increasing restriction of food groups deemed "unhealthy" or "impure"

Unusual interest in what others are eating and controlling family meals

Spending excessive time researching, cataloging, measuring, and weighing food

Feeling anxious or guilty when eating "forbidden" foods

Believing that certain foods can prevent or cause disease despite evidence

For burnout-prone high-achievers, orthorexic tendencies often overlap with perfectionism and may intensify during high-stress periods as a coping mechanism.

Expert Perspective: Pooja Lakshmin, author of Real Self-Care, notes that "what begins as an attempt to feel better through food can quickly become another source of stress when rigid rules replace body attunement."

Exercise Dependency and Compulsive Movement

Similarly, exercise can cross from healthy habit to harmful obsession when:

Workouts are performed despite illness, injury, or extreme fatigue

Anxiety, guilt, or irritability occurs when unable to exercise

Exercise takes precedence over work, relationships, or self-care

The amount needed to feel satisfied continuously increases

Workouts become rigid and joyless, focused only on caloric output

Research Perspective: A 2017 study in Sports Medicine found that exercise dependence was more common among individuals with certain personality traits—including perfectionism and high achievement orientation—that also predispose to burnout (Lichtenstein et al., 2017).

Breaking the Control Cycle

Recognizing when healthy habits have become rigid control mechanisms requires honest self-reflection:

Assess flexibility: Can you adapt your nutrition and movement practices when life circumstances change?

Check motivation: Are you exercising/eating from fear or from care?

Consider impact: Are these habits enhancing or detracting from your overall quality of life?

Evaluate thoughts: Do you experience black-and-white thinking about "good" and "bad" foods or workouts?

Expert Perspective: The team at Mind Pump frequently discusses how sustainable fitness comes from finding the minimum effective dose rather than the maximum tolerable volume—a perspective that naturally counters the control-seeking tendency to do more.

The Fastest Path to the Body You Want: Counterintuitive Truths

Despite what diet culture and "no pain, no gain" fitness messaging suggests, the most efficient path to physical wellbeing involves less restriction and more recovery than most high-achievers initially believe.

Sleep: The Foundation of Metabolism

Dr. Peter Attia frequently states that sleep is the foundation of all health interventions—not a single metabolic pathway in the body functions optimally with insufficient sleep. Research shows that just one night of poor sleep:

Increases hunger hormones and decreases satiety signals

Reduces insulin sensitivity

Impairs post-workout muscle protein synthesis

Decreases motivation for physical activity

Increases cortisol and inflammatory markers

For high-achievers battling burnout, prioritizing sleep quality and quantity is not indulgent—it's the most direct path to both cognitive and physical performance. I've collected practical sleep optimization strategies in my sleep and burnout recovery guide that has helped many of my clients break through plateaus.

Protein: The Metabolism Misconception

Dr. Gabrielle Lyon's work on "muscle-centric medicine" highlights how adequate protein intake supports:

Metabolic health through increased muscle mass

Stable blood sugar and reduced cravings

Greater satiety with fewer total calories

Improved recovery from both physical and mental stress

Better immunity and hormonal health

Many people—particularly women—significantly under-consume protein while over-emphasizing cardio, creating a perfect storm for muscle loss and metabolic slowdown.

Research suggests most active adults benefit from 1.6-2.2g of protein per kg of body weight daily, distributed across 3-4 meals, with higher needs during periods of stress or for individuals over 40.

Walking: The Underrated Tool

While high-intensity exercise dominates fitness marketing, research increasingly shows that simply walking delivers substantial health benefits with minimal recovery cost:

Improved insulin sensitivity

Enhanced creativity and problem-solving

Nervous system regulation

Lymphatic system support

Better sleep quality

Decreased anxiety

For individuals in Stage 1-3 burnout, replacing some higher-intensity exercise with daily walking may actually accelerate progress toward body composition goals by reducing overall stress load and improving recovery capacity.

Recovery: The Missing Link

The Mind Pump team frequently discusses how recovery capacity—not exercise tolerance—is the true limiting factor in physical transformation for most people, particularly those with demanding careers and family responsibilities.

Recovery practices that accelerate progress include:

Deliberate relaxation techniques

Strategic nutrition around workouts

Sleep optimization

Stress management

Full rest days between challenging workouts

Deload weeks every 4-8 weeks

Research Perspective: A 2018 study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that sufficient recovery time between training sessions was more predictive of positive body composition changes than training volume or intensity (Schoenfeld et al., 2018).

The Scarcity Mindset: How Restriction Fuels Burnout

One of the most insidious connections between nutrition, movement, and burnout involves the psychological state of perceived scarcity. When we restrict food or overtrain, we activate the same neurological pathways involved in stress and survival threat responses.

The Biology of Perceived Scarcity

From your body's perspective, energy restriction (whether through diet or overexercise) represents a survival threat that:

Increases stress hormone production

Triggers resource-conserving adaptations

Heightens food reward sensitivity

Increases anxiety and vigilance

Promotes black-and-white thinking

These biological responses made perfect sense for our ancestors facing genuine food scarcity but become problematic in modern contexts where restriction is voluntary and chronic.

The Psychological Impact

Psychologically, operating from a scarcity mindset:

Narrows focus to immediate concerns

Reduces cognitive bandwidth for creative problem-solving

Impairs decision-making quality

Diminishes capacity for self-compassion

Increases likelihood of all-or-nothing behaviors

Research Perspective: Researchers Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir have documented how scarcity of any resource—time, money, food, energy—impairs cognitive function in ways that paradoxically make scarcity more likely to persist.

Breaking the Cycle

For high-achievers prone to burnout, recognizing and countering scarcity-based approaches to health is essential:

Shift from restriction to addition: Focus first on adding nourishing foods and enjoyable movement rather than eliminating or restricting

Practice abundance thinking: Ask "what would this look like if it were easy?" rather than assuming health requires struggle

Budget energy like money: Allocate your physical and mental resources intentionally, with planned reserves

Prioritize recovery: View rest as productive rather than indulgent

Expert Perspective: Sarah Vossen discusses on the Fried Podcast how "the fastest way out of burnout is rarely by doing more, even if that 'more' seems healthy on the surface. It's by strategically doing less and rebuilding your foundation."

Practical Applications: Matching Your Approach to Your Burnout Stage

Let's translate these principles into practical daily approaches based on your current burnout stage. For more detailed recovery plans, check out my burnout recovery roadmap which provides stage-specific guidance.

Stage 0 (Regulated): Performance Optimization

Nutrition Approach:

Strategic meal timing around workouts

Protein at each meal (30-40g)

Carbohydrate cycling based on activity levels

Seasonal whole foods focus

Occasional nutritional challenges if desired

Movement Approach:

Structured progressive resistance training 3-5x weekly

Strategic cardio based on goals

Skill development in chosen activities

Recovery weeks every 6-8 weeks

Daily non-exercise movement

Recovery Approach:

7-9 hours of quality sleep

Stress management practices

Regular social connection

Time in nature

Full rest day weekly

Stage 1 (Sympathetic Activation): Strategic Moderation

Nutrition Approach:

Regular meals every 3-4 hours

Slightly increased carbohydrates, especially around workouts

Emphasis on magnesium-rich foods

Limited caffeine before noon only

No extended fasting

Movement Approach:

Resistance training 2-3x weekly with longer rest periods

Walking as primary cardio

Zone 2 (conversational) cardio if desired

Breath-focused cool-downs after all workouts

Extra recovery days between sessions

Recovery Approach:

8-9 hours sleep opportunity

Designated wind-down routine

Regular parasympathetic activation (deep breathing, meditation)

Nature exposure daily if possible

Technology boundaries

Stage 2 (Functional Freeze): Gentle Regulation

Nutrition Approach:

Easy-to-digest meals and snacks

Warm, cooked foods rather than raw

Blood sugar stabilization focus

Anti-inflammatory emphasis

Mindful eating practices

Movement Approach:

Nature walking

Gentle yoga focused on parasympathetic activation

Basic resistance movements with breath emphasis

Tension-releasing practices (gentle shaking, self-massage)

Movement snacks throughout day rather than longer sessions

Recovery Approach:

Sleep as top priority

Regular nervous system regulation practices

Social connection without performance pressure

Designated technology-free times

Professional support if available

Stage 3 (Dorsal Vagal Collapse): Fundamental Rebuilding

Nutrition Approach:

Small, frequent nutrient-dense meals

Easily digested proteins (bone broth, collagen)

Blood sugar stability as top priority

Elimination of all nutritional stressors

Potential temporary supplementation under guidance

Movement Approach:

Minimal movement threshold only

Recumbent or water-based movement if available

Breath-focused gentle movement

5-15 minute sessions maximum

Multiple rest days between any movement sessions

Recovery Approach:

Maximum sleep opportunity

Professional support strongly recommended

Radical elimination of non-essential demands

Regular parasympathetic nervous system activation

Compassionate boundaries in all areas

Conclusion: Compassionate Performance

The path to sustainable high performance doesn't run through restriction, deprivation, or pushing through signals of burnout. Rather, it emerges from a deep attunement to your body's changing needs and a willingness to adapt your approach accordingly.

For the high-achieving woman juggling career demands, family responsibilities, and personal health goals, or the entrepreneur balancing business growth with physical wellbeing, the most revolutionary act might be matching your expectations to your current capacity rather than the other way around.

Remember:

The body doesn't distinguish between types of stress—work pressure, relationship challenges, restrictive dieting, and overtraining all draw from the same recovery capacity

Women's bodies respond to stress differently than men's, with hormonal cycles providing valuable feedback about overall stress load

The fastest path to physical wellbeing typically involves more sleep, appropriate protein, strategic movement, and substantial recovery—not restriction and intensity

Burnout stage should inform both nutrition and movement approaches, with higher stages requiring more gentle, rebuilding-focused strategies

Unidentified food sensitivities can be hidden stressors keeping your system on high alert

By learning to identify your current burnout stage and match your nutrition and movement practices accordingly, you create the conditions for genuine resilience—not the brittle "pushing through" that so often leads to collapse, but the sustainable capacity to rise to challenges while honoring your body's wisdom.

This isn't about lowering your standards or abandoning your goals. It's about reaching them through the most efficient path: one that works with your biology rather than against it. If you're ready to create a personalized burnout recovery plan, my coaching resources can help you get started.

Note: This article provides general information and is not intended as personalized medical advice. Always consult healthcare professionals before making significant changes to diet or exercise routines, particularly if you have existing health conditions or are experiencing severe burnout symptoms.

References

Aschbacher, K., O'Donovan, A., Wolkowitz, O. M., Dhabhar, F. S., Su, Y., & Epel, E. (2013). Good stress, bad stress and oxidative stress: Insights from anticipatory cortisol reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(9), 1698-1708.

Bjørklund, G., Dadar, M., Pen, J. J., Chirumbolo, S., & Aaseth, J. (2019). Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): Suggestions for a nutritional treatment in the therapeutic approach. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 109, 1000-1007.

Cadegiani, F. A., & Kater, C. E. (2018). Adrenal fatigue does not exist: a systematic review. BMC Endocrine Disorders, 18(1), 1-16.

Davenport, T. E., Stevens, S. R., VanNess, M. J., Snell, C. R., & Little, T. (2010). Conceptual model for physical therapist management of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Physical Therapy, 90(4), 602-614.

Heaton, L. E., Davis, J. K., Rawson, E. S., Nuccio, R. P., Witard, O. C., Stein, K. W., ... & Baker, L. B. (2022). Selected In-Season Nutritional Strategies to Enhance Recovery for Team Sport Athletes: A Practical Overview. Sports Medicine, 52(5), 911-930.

Hynynen, E., Uusitalo, A., Konttinen, N., & Rusko, H. (2011). Heart rate variability during night sleep and after awakening in overtrained athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(4), 684-692.

Lichtenstein, M. B., Griffiths, M. D., Hemmingsen, S. D., & Støving, R. K. (2017). Exercise addiction in adolescents and emerging adults–Validation of a youth version of the Exercise Addiction Inventory. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 182-190.

Madison, A., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2019). Stress, depression, diet, and the gut microbiota: human–bacteria interactions at the core of psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 28, 105-110.

Nagoski, E., & Nagoski, A. (2019). Burnout: The secret to unlocking the stress cycle. Ballantine Books.

Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2018). Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 48(5), 1207-1220.